Identification. In 1502, Columbus stopped near present-day Limón, Costa Rica. Natives with "golden mirrors around their necks" told of "many places . . . [with] gold and mines." Subsequent chroniclers called the region "Costa Rica"—Rich Coast—although it turned out to be among the poorest of Spain's colonies.

Costa Ricans are called ticos, which derives from their appending the Spanish -ico diminutive to the standard -ito.

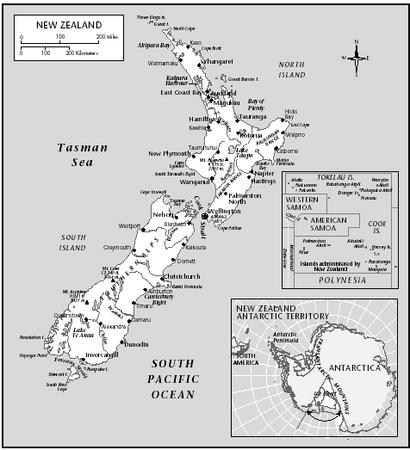

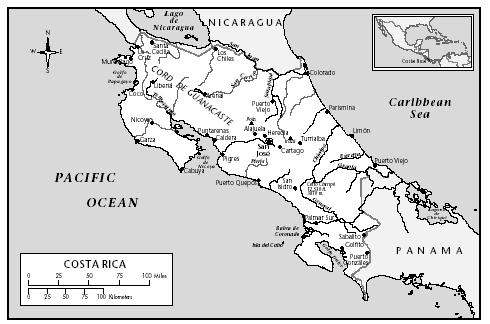

Location and Geography. Costa Rica is located in Central America with Nicaragua to its north and Panama to its south. Its territory is 19,652 square miles (51,022 square kilometers). Volcanic mountains—several of which produce sporadic eruptions— run northwest to southeast, dividing Costa Rica into Pacific and Atlantic zones. There are frequent earthquakes.

The capital, San José, is on the meseta central, a plateau twenty-five miles by twelve miles (40 kilometers by 20 kilometers). The meseta is in the Central Valley—an area five times as large as the plateau— which includes three other cities in addition to San José.

Temperature varies with altitude, averaging over 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius) in the coastal lowlands, but only 64 degrees Fahrenheit (18 degrees Celsius) at the higher elevations. The Atlantic zone receives trade winds and has high rainfall year-round. The Pacific zone has fertile volcanic and alluvial soils and distinct wet and dry seasons. The northern Pacific suffers frequent droughts, associated with the Niño phenomenon.

There are many rivers, but few are navigable. Pacific ports include Puntarenas, Quepos, and Golfito. Two modern ports, Caldera and Punta Morales, were built near Puntarenas in the 1980s. The major Atlantic port, Limón, is unprotected from tropical storms. Moín, north of Limón, has container and petroleum facilities.

Costa Rica's broken topography creates myriad microenvironments. One-quarter of the territory endures practically in its wild state with rainforests, dry tropical forest, and savannas. Costa Rica has a level of biodiversity—4 to 7 percent of the world total—unmatched by any other nation its size.

Demography. In 2000, Costa Rica's population was four million, with 60 percent living in the Central Valley in and around Cartago, San José, Heredia, and Alajuela. Thirty-two percent of the population was 14 years old or under, while 5 percent was 65 or older. Annual population growth was 2.03 percent.

The country had 21.9 births and 4.0 deaths per 1,000 population in 2000, and a net migration rate of 2.4. Average fertility was 2.7, down from 5.4 in 1973 and 7.3 in 1960. The drop in birth rates was attributed to rising female literacy, to a decline in the proportion of the population working in agriculture, and to increased access to family planning. Despite the influential Catholic Church's opposition to contraception, in 1990, 86 percent of sexually active women of childbearing age used birth control.

Linguistic Affiliation. Spanish is the official language, but the variant spoken has features particular to Costa Rica. On the Atlantic coast, however, descendants of Caribbean immigrants speak English, as do many others throughout the country who learned it to better their employment prospects.

Symbolism. The national flag, a partial imitation of the French tricolor, consists of blue horizontal stripes on the top and bottom of the flag and two white inner stripes divided by a wide red stripe, which contains the national coat of arms to the left of center. Aside from the flag and religious icons, important symbols include flags of the major political parties (green and white for the National Liberation Party; red and blue for the Social Christians) and of the most popular soccer teams.

H ISTORY AND E THNIC R ELATIONS

Emergence of the Nation. Costa Rica gained independence from Spain as part of the Mexican Empire (1821–1823) and the Central American Federation (1823–1838). In 1824 it annexed much of the province of Guanacaste from Nicaragua. In the 1850s, Costa Rican troops joined Nicaraguans and Hondurans to defeat William Walker's pro-slavery filibusters. This campaign sparked proto-nationalist sentiment, and it was only then that the term nación began to be used to refer to Costa Rica rather than to all of Central America.

National Identity. Elites had to improvise a national identity following independence. The main hero of the campaign against the United States filibusters, martyred drummer boy Juan Santamaría, was "discovered" as a national icon decades after the conflict ended. Border disputes with Nicaragua and Colombia (to which Panama belonged until 1903) fanned feelings of distinctiveness in the late nineteenth century, as did the creation of a national school system.

Costa Ricans pride themselves on having a society "different" from the rest of Central America. They point to their country's high levels of education and health, its renowned national parks, and its history of democracy and political stability. Despite this "exceptionalism," the country shares many social, economic, and environmental problems with its neighbors.

Ethnic Relations. As much as 95 percent of Costa Ricans consider themselves "white." "Whiteness" figures importantly in national identity. The indigenous population that survived the conquest was small and, for the most part, rapidly became Hispanic. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, successful males of African, Indian, or mixed ancestry married poorer "Spanish" women, using "whitening" to assure their children's upward mobility. In the nineteenth century, immigration from Europe and the United States "whitened" the population, particularly the elite. During the twentieth century, the definition of "whiteness" became more inclusive, as elites sought to convince mestizos that they were part of a "homogeneous" nation distinct from the "Indians" elsewhere in Central America.

In Guanacaste and northern Puntarenas, much of the population is descended from Indians and colonial-era slaves. They are Hispanic in culture and language, though their pronunciation resembles Nicaraguan more than central Costa Rican Spanish.

Concentrated in Limón Province, Afro-Costa Ricans—the descendants of Jamaican and other British West Indians who immigrated in the nineteenth century for work on the Atlantic Railroad, plantations, and docks—are more widely perceived as "black." (These Afro-Costa Ricans are part of an English-speaking Protestant group extending along the entire Caribbean coast of Central America.) Blacks—denied Costa Rican nationality until 1948—were blocked by law and discrimination from working elsewhere, so Limón remained culturally distinct until the mid-twentieth century.

On the Atlantic side of the Talamanca mountains, the Bribri and Cabécar—the largest indigenous groups—speak related languages and share a culture that varies only slightly from one locality to another, depending on the degree of contact with Hispanic society. They maintain clan marriage rules, collective agricultural production, and a religion centered around the deity Sibö the Creator. The six reserves on the Pacific side of the Talamanca cordillera and in the nearby lowlands also are home to the Bribris and Cabécares and to smaller numbers of Borucas (or Bruncas) and Teribes (or Térrabas), the latter two groups having assimilated into the peasant population.

Guaymí Indians live in southern Puntarenas. Many move between these communities and Panama, and until 1991 those born in Costa Rica lacked identity documents and access to state services. The Guaymíes maintain their language and distinct way of life, despite growing reliance on wage labor.

At the end of the twentieth century, five hundred Indians—descendants of a group that numbered well over one thousand in the late nineteenth century—lived in the north along the Río Frío in Alajuela Province. The Guatusos (or Malecus) violently repulsed outsiders' incursions until the 1870s when rubber tappers began to kill Indian men and kidnap women and children, who were sold as slaves in Nicaragua. The population plummeted to below two hundred, never recovering even half its pre-contact size.

Matambú, in Guanacaste, is the only indigenous reserve in the northern Pacific area once populated by peoples whose culture resembled that of central Mexico. The Chorotegas practiced maize agriculture and were among the first targets of the Spanish conquest in the area that became Costa Rica. Culturally, members of the Matambú community are indistinguishable from the surrounding peasantry, participating in saints' brotherhoods (something emblematic of "Indian" identity) and producing ceramics with indigenous motifs for tourists.

Many of the first Spanish colonists in Costa Rica may have been Jewish converts to Christianity who were expelled from Spain in 1492 and fled to colonial backwaters to avoid the Inquisition. The first sizable group of self-identified Jews immigrated from Poland, beginning in 1929. From the 1930s to the early 1950s, journalistic and official anti-Semitic campaigns fueled harassment of Jews; however, by the 1950s and 1960s, the immigrants won greater acceptance. Most of the 2,000 Costa Rican Jews today are not highly observant, but they remain largely endogamous.

In 1873 the Atlantic Railroad imported 653 Chinese indentured laborers, hoping to duplicate the success of rail projects that used Chinese labor in Peru, Cuba, and the United States. Many Chinese fled the snake-infested lowlands, while others died from malaria, landslides, and overseers' brutality. In 1897 the government banned Chinese immigration and anti-Chinese feeling did not subside until World War II.

Other Central Americans had long come to Costa Rica to work in agriculture, especially in the banana zones. In the 1980s, Nicaraguans and Salvadorans fled violence and economic crises to work as farmhands, laborers, servants, and street vendors.

Many foreigners have taken advantage of the Pensionado Law, which grants residency to investors and exempts them from import duties. Most are retired United States citizens, but Chinese, Iranians, Arabs, Europeans, and Latin Americans also settled in Costa Rica under this law.

By the late twentieth century, allusions in textbooks and political discourse to "whiteness," or to Spain as the "mother country" of all Costa Ricans, were diminishing, replaced with a recognition of the multiplicity of peoples that make up the nation.

U RBANISM ,A RCHITECTURE, AND THE U SE OF S PACE

Almost all towns have a central plaza with a Catholic church, government buildings, bandstand, and benches. Rural villages have grassy squares that double as soccer fields. Beyond the downtown grids are "urbanizations" that resemble U.S. subdivisions and then rural homesteads. There is little notable architecture aside from San José's ornate neo-classical National Theater. Few colonial constructions survive, and many contemporary buildings would elsewhere be considered kitsch. The cities suffer from severe air, water, and noise pollution.

F OOD AND E CONOMY

Food in Daily Life. Maize is consumed as tortillas, which accompany rice and beans—typically eaten three times a day with eggs, cheese, meat, or chicken and with chayote stew or salad at lunch or supper. The midday meal was once the largest, but the long lunch break has succumbed to a fondness for fast food.

Beverages include coffee, sugary fruit drinks, and soda. Alcohol consumption is high.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Salty appetizers are served at parties and at bars and restaurants. Maize tamales are prepared by hand for Christmas. Other special occasions (birthdays, graduations, marriages) may merit a roasted pig, an elaborate cake, or other sweets.

Basic Economy. Until the 1960s, Costa Rica depended on coffee and bananas for most of its export earnings. Coffee income was well distributed, which fueled a dynamic commercial sector. After the 1948 Civil War, nationalized banks channeled subsidized loans to neglected regions and new activities. In the 1960s, beef and sugar assumed greater importance, and the country began to industrialize, protected by Central American Common Market tariffs. Following a debt crisis in the early 1980s, the state reduced its role in the economy and promoted export-oriented agriculture and industries. Since the late 1990s, tourism has been the second largest source of dollars, after bananas.

Land Tenure and Property. Costa Rica has an image as an "agrarian democracy," but land distribution is highly unequal. Coffee farms are mostly

Commercial Activities. City and town residents now rely on supermarkets rather than neighborhood stores and farmers' markets. Growing consumerism has spurred construction of malls where the affluent acquire the latest fashions and gadgets and the poor come to gawk and marvel at the high prices.

Major Industries. Since the mid-1980s, Costa Rica has become a center for factories that assemble garments, electronic components, and other goods for export. Other key manufactures include baseballs, agricultural chemicals, and processed foods. The economy is increasingly integrated into global circuits of trade, production, and finance.

Trade. Coffee and bananas are the country's chief agricultural exports, along with beef, sugar, flowers, nuts, and root vegetables.

Division of Labor. The economy diversified after 1950, and new groups emerged. In 1997, agriculture accounted for 19 percent of employment and 15 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), under half of 1950 levels.

S OCIAL S TRATIFICATION

Classes and Castes. Many upper-class families are descended from a few Spanish conquistadores. Levels of interaction between social classes were nonetheless high well into the twentieth century. Members of prominent families intermarried with other groups, especially wealthy European, Latin American, and North American immigrants. In Guanacaste and northern Puntarenas more rigid patterns of class relations are the norm.

The coffee elite, which dominated politics and society from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, derived most of its wealth from coffee processing and the export trade, not from ownership of plantations. Coffee also gave rise to a rural middle class. The Costa Rican middle class constitutes a larger proportion of the population— perhaps one-quarter—than in other Central American countries.

Costa Rica is no longer a country of peasants. The opening of the University of Costa Rica in 1940 and the expansion of the public sector after 1948 provided new opportunities for upwardly mobile young people. Yet poverty remained significant, affecting one-fifth of the population at the close of the twentieth century. Nonetheless, in 1999, the United Nations ranked Costa Rica fourth among developing nations worldwide that have made progress in eliminating severe poverty.

Symbols of Social Stratification. The culture of consumption—in which clothes, cars, houses, and trips abroad are markers of status—is most conspicuous among members of the upper middle class, roughly 10 percent of the population.

P OLITICAL L IFE

Government. The government has four branches: the executive, the unicameral Legislative Assembly, the judiciary, and the Supreme Electoral Tribunal. In addition, many autonomous public sector institutions were created in the 1960s and 1970s. Most were privatized, downsized, or abolished in the 1980s and 1990s.

Leadership and Political Officials. Presidential and legislative elections are held every four years. Presidents generally appoint cabinet ministers and many other central government officials and employees. Legislative deputies consolidate support through dispensing special budget appropriations (partidas específicas) in their districts.

Costa Ricans are passionate about party loyalties, which often run in families and generally date to the 1940s when a social democratic insurgency overthrew a Catholic-Communist reformist coalition government and ushered in the modern welfare state. The National Liberation Party (PLN) was social democratic, but embraced free-market policies in the 1980s. The Social Christian Unity Party (PUSC) has roots in social Christian reformism, but became more conservative than the PLN. Leftist parties declined. Regionalist parties occasionally elected legislative deputies or local officials.

Social Problems and Control. With the economic crisis of the early 1980s, violent street crime skyrocketed and remains high today. Firearms from wars elsewhere in Central America were easily acquired. Costa Rica became a transshipment point for Colombian cocaine bound for the United States. The emergence of private financial institutions in the 1980s facilitated money laundering.

Military Activity. The military was abolished following the 1948 Civil War. Security forces include the Civil Guard, Rural Guard, Judicial Police, and several smaller intelligence units. Private guards protect businesses and middle- and upper-class communities.

In the 1970s and 1980s, northern Costa Rica served as a base for armed Nicaraguan Sandinistas and then for anti-Sandinistas.

S OCIAL W ELFARE AND C HANGE P ROGRAMS

Costa Rica has made remarkable strides in improving living standards. Most Costa Ricans enjoy access to free health care, basic education, and social services. Free-market policies have forced reductions in spending, but health and education indicators remain impressive.

N ONGOVERNMENTAL O RGANIZATIONS AND O THER A SSOCIATIONS

Costa Rica hosts dozens of nongovernmental organizations, many of which operate throughout Central America. The business elite is organized in sectoral cámaras (chambers), which exercise enormous political influence. Public-sector and banana-worker unions were important until the 1980s.

G ENDER R OLES AND S TATUSES

Division of Labor by Gender. Women are still responsible for food preparation, childcare, and cleaning. Men rely on mothers and wives or hired help. The middle and upper classes employ servants for housework and childcare. Heavy agricultural labor is performed by men and adolescent boys. Women harvest coffee, cotton, and vegetables.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Gender relations are similar to those elsewhere in Latin America, although women have achieved greater equality than in some other countries. "Macho" practices—flirtatious remarks on the street, physical violence in the home—are widespread.

Gender relations are in flux, with marked differences between generations and social groups. Women increasingly combine traditional responsibilities with work and education. Men dominate business and politics, but many women have held cabinet posts or are prominent in arts and professions. A 1994 Law for Promoting the Women's Social Equality prohibited discrimination and established a women's rights office.

M ARRIAGE ,F AMILY, AND K INSHIP

Marriage. Costa Ricans' median age at first union is twenty-one for women and twenty-four for men. Premarital sex, expected of men, has become more common for women. Divorce and separation are frequent. Many upper-class men maintain mistresses and second families. The National Child Welfare Board garnishes wages of men who fail to pay child support and blocks them from traveling abroad.

Domestic Unit. Most families are in practice extended, with elderly or other kin in the household and other relatives nearby. Female-headed, multi-generational households are common among the poor.

Inheritance. Costa Ricans use their fathers' and mothers' last names to reckon descent. Inheritance is partible, but practiced with flexibility. Since 1994, the property of unmarried couples must be registered in the woman's name.

S OCIALIZATION

Infant Care. Infants are dressed warmly, because "air" is considered harmful. Girls have their ears pierced shortly after birth. Almost half of mothers no longer breast feed. Most parents request that a friend or affluent neighbor be a godparent to their newborn.

Child Rearing and Education. Children are treated with indulgence until age four or five, when they tend to be disciplined more consistently. Disciplinary practices vary greatly, from corporal punishment to withholding treats. Poor children often help with chores at an early age. Primary school attendance is universal; secondary school enrollment rates are very high. The educational system emphasizes rote learning and memorization, rather than analytical thinking. The adult literacy rate is 95.1 percent (1997).

Higher Education. One-quarter of the universityage population enrolls in higher education. Four public universities enroll four-fifths of the students; the rest attend three dozen private institutions. The undergraduate curriculum consists of a year of education in liberal arts and sciences followed by three or four years of specialized courses, leading to a university bachelor's degree. Students may opt for a year of additional work, involving a written thesis, that leads to a licenciatura, the main credential required for most advanced positions. Medicine and law are undergraduate careers.

E TIQUETTE

Costa Ricans consider themselves "cultured" and polite. Children, parents, and age-mates are often addressed in the formal second-person. Men greet each other with a handshake, while women greet female and male friends and relatives with a kiss. Dating and courtship, once highly ritualized, are approaching U.S. patterns. Much socializing goes on in restaurants and bars. Malicious gossip is common and a source of both delight and apprehension.

R ELIGION

Religious Beliefs. The Catholic heritage remains important in everyday language and culture. Cristiano is used as a synonym for "human being." Even those who are not religious like to have a religious medallion or picture of a saint in their cars or homes.

Costa Ricans demonstrate their Catholic faith mainly at baptisms, weddings, and funerals or during

The principal challenge facing Catholicism is the rise of evangelical Protestantism, which now claims the loyalty of more than one-tenth of the population. Adherents report finding the participatory evangelical services more satisfying than staid Catholic liturgy. Converts generally abstain from alcohol and abide by stern codes of conduct.

Religious Practitioners. In the 1940s, the Church was involved in social reform. Following the 1948 Civil War and the defeat of the Catholic-Communist alliance, the Church abandoned activism. The broad reach of the welfare state meant that the Church did not have to be as concerned with social questions as its counterparts elsewhere. Some priests participated in action campaigns among peasants and shantytown dwellers, but most Church institutions remained conservative, with the Catholic hierarchy keeping a low profile.

Rituals and Holy Places. On the eve of the 2 August celebration for the national patron saint— Our Lady of the Angels—pilgrims throughout the country fulfilling "promises" to her hike to Cartago's Basílica of Our Lady of Los Angeles. Most churches sponsor local saints' celebrations, which are smaller and more secular in comparison with the national holiday for Our Lady of Los Angeles.

Death and the Afterlife. Catholics are typically buried following a church funeral. Wakes are held in the home of the deceased or in a funeral parlor. When a middle- or upper-class person dies, family members and associates place condolence advertisements in newspapers. Masses are held and rosaries recited at regular intervals after the event.

M EDICINE AND H EALTH C ARE

Costa Rica leads Central America in health, largely because of the extension to the entire population of free care through the Health Ministry and Social Security System. (The affluent, however, prefer to use private clinics.) Costa Rica's disease profile increasingly parallels that of industrialized societies. By the early 1990s, Costa Rica had as many doctors per one thousand population as the United States.

S ECULAR C ELEBRATIONS

Secular celebrations occur at regular intervals— election days, soccer championships—and when a Costa Rican team or individual attains international prominence. Festivities are marked by caravans of automobiles flying flags and blaring horns.

Middle- and upper-class girls often have fifteenth-year celebrations marking their formal entrances into society. Rodeos, with equestrian and bull-riding competitions, are held in many towns, sometimes in connection with religious celebrations.

T HE A RTS AND H UMANITIES

Support for the Arts. Beginning in the 1950s, the state provided extensive support for the arts and arts education, funding a National Symphony and Youth Orchestra, a major publishing house, dance and theater troupes, and several major museums, as well as offering awards and prizes in numerous fields. With the economic cut backs that began in the 1980s, the Ministry of Culture's budget plummeted, although many arts institutions and artists have managed to survive through private donations, concerts or gallery sales, and tourist patronage.

Literature. In the early twentieth century, Joaquin Garcia Monge edited the literary journal Repertorio Americano, which was widely read throughout Latin America. Costa Rica's most distinguished early twentieth-century writers, such as novelists Carlos Luis Fallas, Joaquin Gutiérrez, Fabián Dobles, and Luisa González, as well as more contemporary ones, such as novelists Carmen Naranjo and Alfonso Chase and poet Jorge Debravo, have focused on social protest as a major theme. Political essays and biographies are also quite common, traditionally, as is sentimental, regionalist fiction that evokes a largely problem-free, idyllic past.

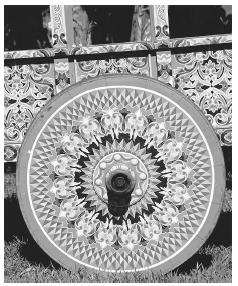

Graphic Arts. Costa Rica has little of the artisan or craft production so noticeable in Mexico or Guatemala. The "traditional" painted oxcart that is featured in tourist shops actually dates only to the early twentieth century.

Graphic artists Francisco Amighetti, Manuel de la Cruz González, and Margarita Berthau are among those who have attained an international following. Sculptor Francisco Zúñiga also has an international reputation, although he lived most of his life in Mexico and emphasizes Mexican topics in his work.

Performance Arts. The world of Costa Rica drama expanded significantly in the 1970s with the arrival of exiled Argentine and Chilean actors, playwrights, and directors, who founded new theater companies that had a more contemporary and broader repertoire. Several small theater companies have significant public followings, as do the productions staged at the major universities. In addition to the small, but vibrant, classical music scene, there are several folk groups devoted to Latin American "new song" and to recording and performing the country's vanishing heritage of Caribbean calypso, Spanish-style peasant ballads, and labor songs. American-, Brazilian-, and Cuban-influenced jazz combos enjoy a small but dedicated following. Modern dance has become popular since the 1970s, reflecting in part a breakdown of traditional inhibitions about exhibitions of physicality and the body.

T HE S TATE OF THE P HYSICAL AND S OCIAL S CIENCES

The University of Costa Rica is the main research institution. Other public universities are the Technological Institute, the National University— whose religion department became an important center for Latin American liberation theology advocates—and the State University at a Distance, which provides correspondence courses. Specialized institutions include the Central American Business Administration Institute, the Peace University, and the Center for Tropical Agronomic Research and Teaching. Since the mid 1980s, private universities have proliferated, specializing in law, business administration, tourism, and technical programs.

B IBLIOGRAPHY

Biesanz, Mavis Hiltunen, Richard Biesanz, and Karen Zubris Biesanz, The Ticos: Culture and Social Change in Costa Rica, 1998.

Bozzoli de Wille, María E. El indígena costarricense y su ambiente natural, 1986.

Chomsky, Aviva. West Indian Workers and the United Fruit Company in Costa Rica 1870–1940, 1996.

Edelman, Marc. The Logic of the Latifundio: The Large Estates of Northwestern Costa Rica Since the Late Nineteenth Century, 1992.

——. Peasants Against Globalization: Rural Social Movements in Costa Rica, 1999.

——, and Joanne Kenen (eds.). The Costa Rica Reader, 1989.

Evans, Sterling. The Green Republic: A Conservation History of Costa Rica, 1999.

Gudmundson, Lowell. Costa Rica Before Coffee: Society and Economy on the Eve of the Export Boom, 1986.

Honey, Martha. Hostile Acts: U.S. Policy in Costa Rica in the 1980s, 1994.

Janzen, Daniel H. (ed.) Costa Rican Natural History, 1983.

Lara, Silvia, Tom Barry, and Peter Simonson. Inside Costa Rica: The Essential Guide to its Politics, Economy, Society, and Environment, 1995.

Leitinger, Ilse Abshagen (ed.). The Costa Rican Women's Movement: A Reader, 1997.

Molina, Iván, and Steven Palmer. The History of Costa Rica: Brief, Up-to-Date and Illustrated, 1998.

Morales, Abelardo, and Carlos Castro. Inmigración laboral nicaragüense en Costa Rica, 1999.

Palmer, Steven. "Getting to Know the Unknown Soldier: Official Nationalism in Liberal Costa Rica, 1880–1935." Journal of Latin American Studies 25 (1): 45– 72, 1993.

Sandoval García, Carlos. Sueños y sudores en la vida cotidiana: Trabajadores y trabajadoras de la maquila y la construcción en Costa Rica, 1996.

Stone, Samuel Z. "Aspects of Power Distribution in Costa Rica." In Dwight Heath, ed., Contemporary Cultures and Societies of Latin America, 1974.

Williams, Robert G. States and Social Evolution: Coffee and the Rise of National Governments in Central America, 1994.

Wilson, Bruce M. Costa Rica: Politics, Economics, and Democracy, 1998.

Winson, Anthony. Coffee and Democracy in Modern Costa Rica, 1989.

—M ARC E DELMAN

Source : http://www.everyculture.com/Bo-Co/Costa-Rica.html